by Maya Wisher

Grandmother Stone, painted by artist Natalie Rostad Desjarlais.

Photo Credit: Emerson Gonzales

On the banks of the Red River in Winnipeg’s North End lies a quiet and powerful place where memory, healing, and hope converge. The Kapabamayak Achaak Healing Forest—meaning “Wandering Spirit” in Anishinaabemowin—is more than a beautiful landscape. It’s a living memorial to those affected by Canada’s residential school system, offering a place of reflection and vision for a brighter future.

“From conception to reality, the group followed three basic guiding themes: connection, community, and creation,” says Ryan Epp, Associate Landscape Architect with ft3 Architecture Landscape Interior Design, a longtime BOMA Manitoba member firm. ft3 was brought on board to help shape and bring the vision of the Healing Forest vision to life, blending landscape architecture, cultural significance, and collaborative design into a cohesive plan.

The idea for the Healing Forest began at a 2017 social justice gathering for educators. After being moved by a presentation on the National Healing Forest Initiative, University of Winnipeg educator Dr. Lee Anne Block declared, “We need a Healing Forest in Winnipeg.” Her colleague, Dr. Debra Radi, agreed—and that spontaneous idea quickly grew into a mission.

Block and Radi connected with former MP Judy Wasylycia- Leis, who hosted an early meeting at Neechi Commons. There, they connected with Kyle Mason, an Indigenous leader and son of a residential school survivor. From that moment on, the project became something bigger.

“The team invited Indigenous Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and community members to shape the vision every step of the way,” says Epp.

Drawing from their experience with commercial landscape design, ft3 approached the project with care and intentionality—centering values of engagement and sustainability, alongside a powerful sense of place. The ft3 team applied the same principles they bring to high-performance commercial landscapes: stakeholder engagement, durability, and site-specific placemaking.

What set the Healing Forest apart was its deep and ongoing public involvement, with open meetings that became settings for truth-telling, storytelling, and shared dreaming.

“There were a lot of stories from the heart,” explains Epp. “A lot of hard truths were shared, but also a deep sense of optimism about what this space could become.”

“We wanted to tread lightly, to let the land guide us.”

The Healing Forest highlights how social responsibility and commercial development are not at odds. Instead, they can complement one another— particularly when developers embed consultation, cultural knowledge, and inclusive concepts early in the planning process.

St. John’s Park was chosen for its accessibility, proximity to schools, and natural serenity—close to Main Street but far enough from the downtown bustle. Its mature trees, riverside setting, and existing trail network made it ideal for quiet reflection and educational gatherings.

Painted Grandmother Stone with Kapabamayak Achaak Healing Forest behind.

Photo Credit: Emerson Gonzales

Developing the forest was a collaborative process. Métis designer Shaun Finnigan created the original concept sketch, envisioning a circular layout inspired by the Medicine Wheel. That sketch served as the conceptual foundation for the framework, refined by the ft3 team through site visits and thoughtful design choices.

“We visited the space quite a bit,” says Epp. “We wanted to tread lightly, to let the land guide us.”

Four quadrants , aligned to the cardinal directions, feature in the final layout. All are surfaced with materials such as crushed granite, clay, and limestone— chosen for their texture, symbolism, and sensory engagement. Locally salvaged oak cants (log segments) provide seating, their growth rings exposed as a symbol of time and resilience.

“These kinds of spaces— they give something back.”

These same principles—durable local materials, symbolic integration, and community-responsive plan—are increasingly being adopted in commercial and institutional landscape design. They not only contribute visual interest and functionality but also help strengthen a development’s identity and connection to its neighbouring area.

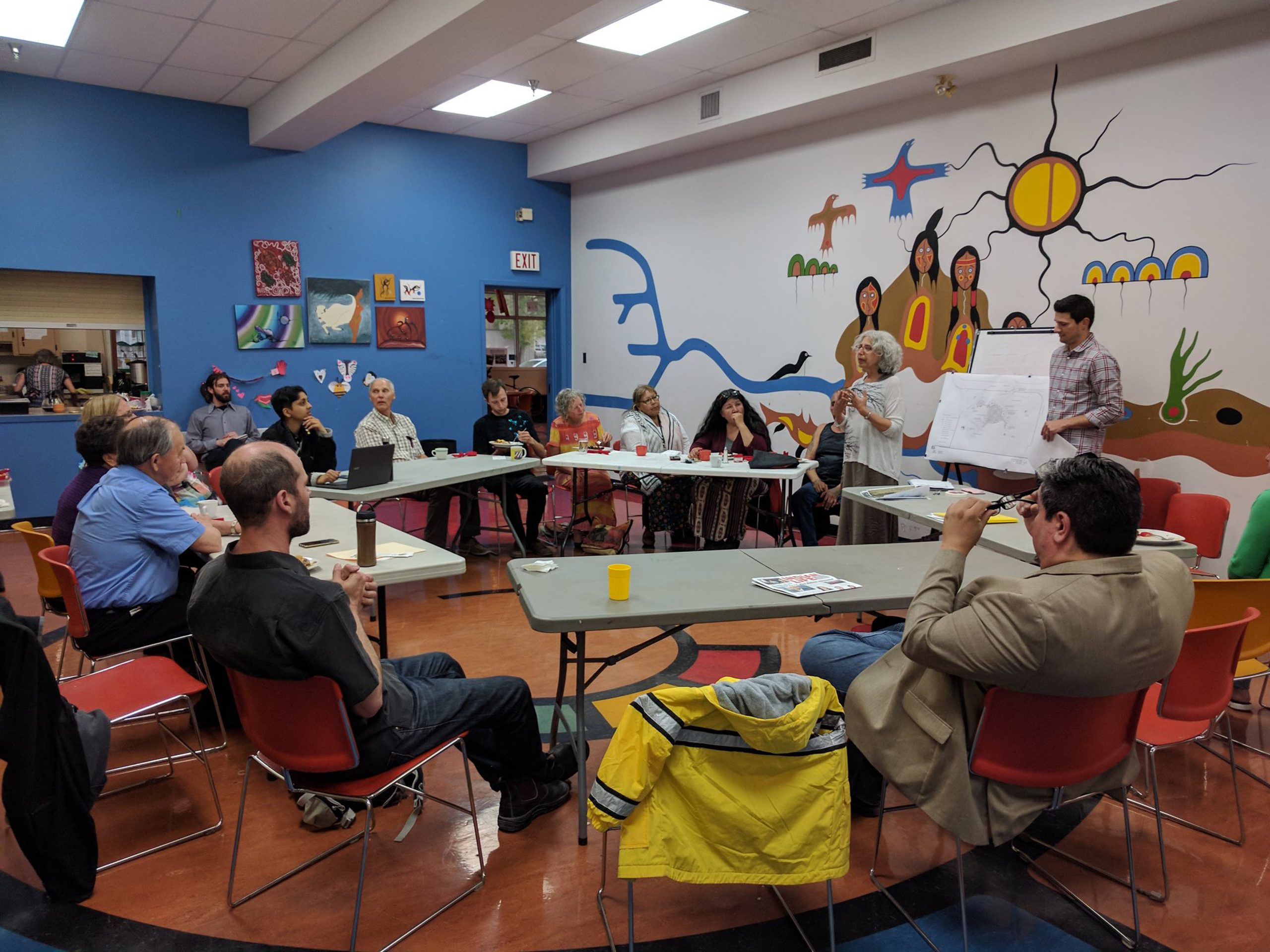

Project team members meeting, led by Dr. Lee Anne Block.

At the heart of the Healing Forest lies a polished granite Medicine Wheel, surrounded by Grandmother Stones—each painted by Indigenous artist Natalie Rostad Desjarlais. Inspired by a media segment about the project, she reached out to contribute her talents. “Each stone has a story to tell,” says Epp. “She sees images within them and brings them to life through her artwork.” Children often explore the stones like a spiritual scavenger hunt, discovering animals, symbols, and stories hidden in the stones’ natural curves.

Like many meaningful projects, the Healing Forest faced its share of challenges. One winter, a funding deadline required the team to plant trees in frozen ground—an almost impossible task. “We suggested the team go ahead and do it,” Epp recalls. “They thought we were a little bit crazy, but we were resourceful and brought in an arborist with a stump grinder to break the frozen ground.” Remarkably, the trees took root and continue to thrive today.

Neighbourhood support has been central to the forest’s success. Students from nearby schools have helped maintain the area. Families have planted trees and perennial beds. St. John’s Anglican Cathedral, located just across the street, opened its doors to school groups needing their facilities or a warm environment.

“There is a real sense of pride within the community for this space,” Epp says.

Even acts of vandalism have been met with creativity. When the central granite stone was damaged by fire, the response was one of resilience, not anger. Renowned Metis artist and Knowledge Keeper Val Vint created a steel plate to cover the damage —incorporating traditional artwork that brought new meaning to the site.

Artist Natalie Rostad Desjarlais selecting Grandmother Stones.

Photo Credit: Emerson Gonzales

The conceptual approach behind the Healing Forest offers a valuable model: sensitive land use, layered storytelling, and a focus on long-term public engagement. Projects like this that incorporate environmental, societal, and governance in their plans can help create a popular and impactful site.

For BOMA members, the lessons are highly transferable. As environmental standards and public engagement become industry norms, projects like the Healing Forest show how reconciliation-focused, inclusive planning can enhance visitor experience, strengthen public trust, and increase long-term value—no matter the scale or setting.

Looking ahead, a second phase is planned, with expanded gathering places, teaching areas, and gardens featuring medicinal plants. But even now, the site is fulfilling its purpose.

“It’s going to take a long time to get over the trauma of the residential school system and its impact,” Epp explains. “But if we reach the kids now, give them the truth—they’re going to carry that forward and teach it to their own kids.”

For those who visit, the Healing Forest is more than a quiet park. It’s a place of listening, of learning, and of presence.

“These kinds of spaces—they give something back,” Epp reflects. “If you have the chance to create landscapes that are both high-quality and meaningful, take it—it’s worth it.”